Women's Education in the South of Yemen prior to 1990

Part 2 of 4

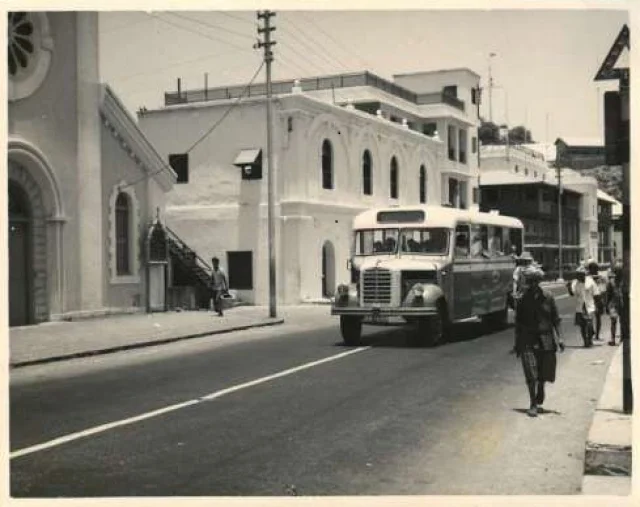

In the past, Yemeni women experienced different realms of education based on the governing power. From 1839 to 1967, women in the south lived in a colonized Yemen under the British Empire. The powerful men of the south, the sultans and sheikhs within various emirates, formed financial relationships with their occupiers to benefit from the British annexation and to maintain hegemony over their regions. The city of Aden and its port were considered part of the British Indies until 1937, when the city became a Crown Colony by itself (‘Ali 30). The port of Aden was useful to the British as a coaling base and provided them with strategic domination over their other colonies (Ghanem 6). Furthermore, the female population of the south was much smaller than that of the north, as the entire population was a mere 1.8 million over a vast 112,000 square miles (Molyneux, “Women and Revolution” 5). The populace was scattered and women’s education was rare and only available in the bustling city of Aden (see map 1).

Map 1: South of Yemen (outlined in blue and red)

Source:Numista. Map. Feb. 2011. Web. 12 Mar. <http://en.numista.com/numisdoc/yemen-26.html>.

In Aden, schools were spread over small townships and were co-educational with the curriculum dictated by the British. In the entire south, more specifically in the township of Khormaksar, only one “girl’s-only” secondary school, known as the Girls’ College, operated. There were two secondary private co-educational institutions: the Order of Saint Francis Convent School and Steamer Point (Noman 1). These schools usually had students of mixed ethnicities; British, Arab and Indian, and males and females interacted intellectually. Unfortunately, families that lived far away from the city of Aden rarely sent their daughters to schools and lived a very traditional and secluded life.

In 1959, the British Empire divided the Colony and designed the outline for the Federation of South Arabia (see map 1) while the emirates that refused to join were part of the Protectorate of South Arabia (‘Ali 33). As the strength of the British Empire weakened, the southern people of Yemen struggled for their own independence. By November of 1967, the National Liberation Front (NLF), a nationalist organization of 26,000 members founded in 1963, was recognized by the British as representative of its own territory and soon after, the south was declared an independent state (Ghanem 4). At this time, the educational data finds by the World Bank were distressing. In 1965, 23% of the total primary school age group were enrolled; while only 10% were girls. In 1970, the adult literacy was a mere 31% of the total adult population and 9% of the women’s population (Boxberger 121). Based on this, a small faction of women received bilingual western education, while the remainder of the female population received no education at all.

The NLF officially united the Protectorates of South Yemen (see map 3) to form the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY) and one of their objectives was to achieve a an enlightened working nation that encompassed males and females equally (Molyneux 5).

Map 3: South Yemen: Governorates, Major Cities, and Major Roads, 1984

Source: Krieger, Laurie, Darrel Eglin, Sally Ann Baynard, Donald Seekins, and Bahman Bakhtiari. The Yemens: Country Studies. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American University, Foreign Area Studies, 1986. 245 Print.

From 1968 to 1978, the PDRY followed the ideology of Karl Marx and abandoned tribal affiliations. The government immediately ended all forms of Feudalism or Iqta’ and distributed lands equally (Ghanem 7). The NLF government, later known as the Yemeni Socialist Party (YSP), implemented rigid planning and restructuring of the region. The PDRY was organized and had a transparent strategy towards female education.

The PDRY and Female Education

The PDRY grew dependent on economic and military support from the former USSR, as it was the only country in the Arabian Peninsula to follow the Marxist doctrine. The new country, although ambitious, was poor and lacked funds from richer Arab countries that resented their ideology and their allies. Regardless of these challenges, the Marxist-Leninist constitution of the country dictated the “full emancipation” of women (Molyneux, “Women and Revolution” 5). In article 35, the constitution states that “[a]ll citizens are equal in their rights and duties irrespective of their sex, origin, religion, language, standard of education or social status” (qtd. in Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 421). “Education for All” was the slogan of the campaign that swept the country after the creation of the PDRY. Regardless of monetary shortages, education was considered an investment by the regime. Through the use of the media, more specifically radio and television, the campaign raised awareness amongst families and emphasized its importance for males and females. The educational program of the PDRY reached every little village in the South by 1984, including the island of Socotra which was usually excluded from most programs (Noman 1).

The system of education was known as “the unity” program which entailed eight years of primary education (see Chart 1 for progress over the years), followed by four years of secondary education. During secondary school, the student (male or female) would chose to participate in one of the following: 1) academic, 2) vocational, 3) technical or 4) teacher trainings, which were tailored more specifically to fit the student’s future career (Noman 2). Following their education, women worked in multifarious jobs ranging from factory workers to judges (Molyneux, “State Policies and the Position of Women Workers”)

Chart 1: Statistics about the “Unity” Educational Program 1966-1990

Year # of Schools # of Students # of teachers

66/67 249 49828 1745

85/85 940 278254 11320

89/90 1039 340042 13744

Source: : Ba'abad, 'Ali. Al-Ta'aleem Fee Al-Jumhooriah Al Yamaniyah [Education in the Yemeni Republic]. 7th ed. Sana'a: Maktabat Al-Irshad, 2003. 127. Print.

Following these educational reforms, southern women were erudite enough to form the Yemeni Women’s Union which was connected to the party and state structures in the south and functioned very similarly to trade unions. This union promoted female agency and positioned a female representative in every rank within the party structure (Molyneux, “Women and Revolution” 6). Providing Yemeni women with formal education corresponded with an increase in female political participation. Maxine Molyneux, a political sociology senior lecturer at the University of London, argues that the PDRY was “arguably the most egalitarian in the Arab world” (“Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 418). The new government recognized women’s rights and considered themselves more progressive than their former British occupiers in their treatment of women;

As far as the official analysis of women’s subordination in the PDRY is concerned the clearest statement on this is contained in a speech by Salem Robaya Ali, the country’s former President, delivered at the First Congress of the Women’s Union in 1974. This begins by deploring the more extreme forms of ‘humiliation, degradation, oppression and exploitation to which women were subjected under ‘colonial and reactionary rule’... The speech went on to denounce the exploitation and oppression of women in the home, the practice of arranged marriages, and the custom of considering women to be worth half a man in law, property rights and employment...Women’s freedom was, however, now possible under socialism and lay ‘in education and in inculcating new traditions that lie in the secret of their love of work and production’. (Molyneux, “Women and Revolution” 7)

The PDRY, a Muslim country, continued to provide improvements in the lives of women by banning arranged marriages, abolishing polygamy (except in cases where the wife was sterile), and facilitating marriages by reducing the bride-price or mahr. Furthermore, talaq (man initiated Islamic divorce) was prohibited and was now a court matter (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 421).

Factors that lead to the Collapse of PDRY

Outside of the capital of Aden, many of the people within the south began protesting the socialist ideology. The country was also attacked externally, where some Muslim and Arab countries accused their administration of being “un-Islamic” even though the PDRY’s constitution recognized Islam as the official state religion. Saudi Arabia financed exile radio stations in the UK to criticize the PDRY as an “atheist” government for allowing women to be judges (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 425). As the government’s grip on things began to weaken, the southerners turned to previous cultural practices. Many women in the PDRY continued to veil and maintained a traditional role at home (Molyneux, “State Policies and the Position of Female Workers” 36). The low bride-price was not monitored and girls’ educational attendance was not enforced outside of the capital and was declining rapidly. These infringements are not surprising, after all, the Marxists ideology was alien to the people of Yemen and the increase in outside opposition and poverty only aggravated the situation. By 1986, the Yemeni PDRY leaders lost their faith in the socialist system and the economy “was loosened, allowing a greater role for private ownership of industry and agriculture...and the role of Islam was enhanced” (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Contingency” 425).

It is important to note that perhaps the PDRY never meant to promote women’s rights per se, but rather communist ideals. Heidi Hartmann, feminist economist and developer of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWRP), explains this relationship best in The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism: Towards a More Progressive Union;

The feminist question is directed at the causes of sexual inequality between women and men, of male dominance over women. Most marxist analyses of women’s position take as their question to the relationship of women to the economic system, rather than that of women to men, apparently assuming the latter will be explained in their discussion of the the former...Defining women as part of the working class, these analyses consistently subsume women’s relation to men under workers’ relation to capital. (172-173)

The Marxist system may serve feminist objectives except it always controls its development. Overall, it allowed females there a period of brief exposure to equality in education.

Next piece: Women's Education in the North of Yemen prior to 1990.