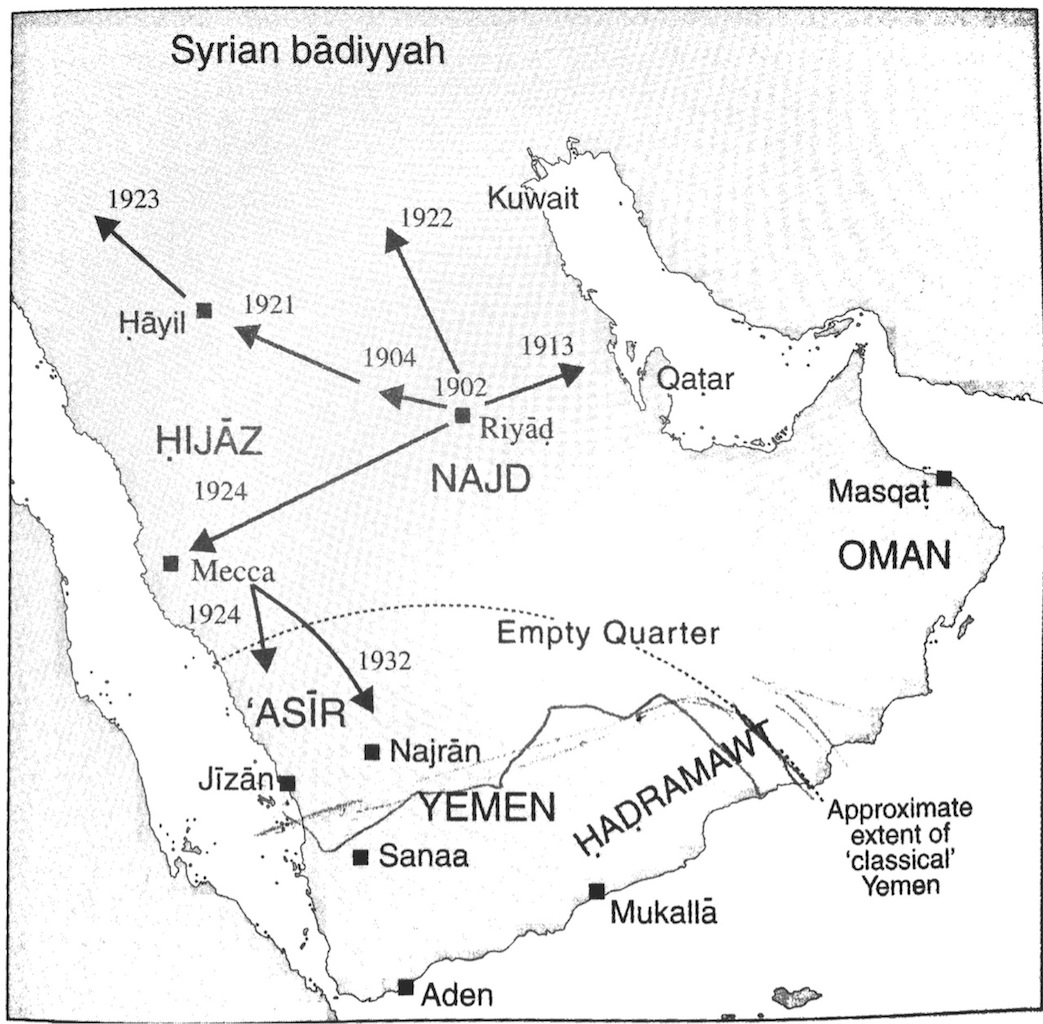

Map 3: Saudi Expansion and “Classical” Yemen

Source: Dresch, Paul. A History of Modern Yemen. Cambridge: Cambridge United Press, 2000. 33. Print.

Under the Imamate, formal education did not develop much and carried on according to how the Ottomans have left it (i.e. no ministry of education or formal unified curriculum). Regardless, some progress occurred in boys’ education where Dar Al-'Ulum (House of Science) and a public library was created in 1919, bearing in mind that the majority of students never completed middle school or high school. By 1949, The North of Yemen had a total of 535 schools; one of them for females (see chart 2 for the breakdown of schools). Girls in elite families went to al-mu’alaamah (a form of Islamic school) where they memorized the Qur’an for a few years and in 1949, a special school was founded to teach girls home economics and sewing (Ba’abad 51-67). Generally, schools were located in urban areas and were scarce in rural areas which required boys to make long commutes to classes (Noman 2). Of course, due to the conservative nature of the North, girls were not allowed to travel that far without constant male supervision.

Chart 2: School Classifications in 1957

Source: Ba'abad, 'Ali. Al-Ta'aleem Fee Al-Jumhooriah Al Yamaniyah [Education in the Yemeni Republic]. 7th ed. Sana'a: Maktabat Al-Irshad, 2003. 68. Print.

The Imamate which ruled like an isolationist monarchy faced a lot of opposition and by 1962, the people of Yemen overthrew Imam Muhammed Al-Badr. While the south was inspired by Marx, the North was inspired by Egypt’s Nasser who promoted an ideology of Arab Nationalism. At the end, the revolutionaries proved stronger and the Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) was created (see map 4). By 1970, Saudi Arabia officially recognized the new government which put an end to the Imamate (‘Ali 47). When the YAR took control, education in the north was ghastly. According to data provided by the World Bank in 1965, only 9% of total number of primary school age group were enrolled, with 1% female (Boxberger 121).

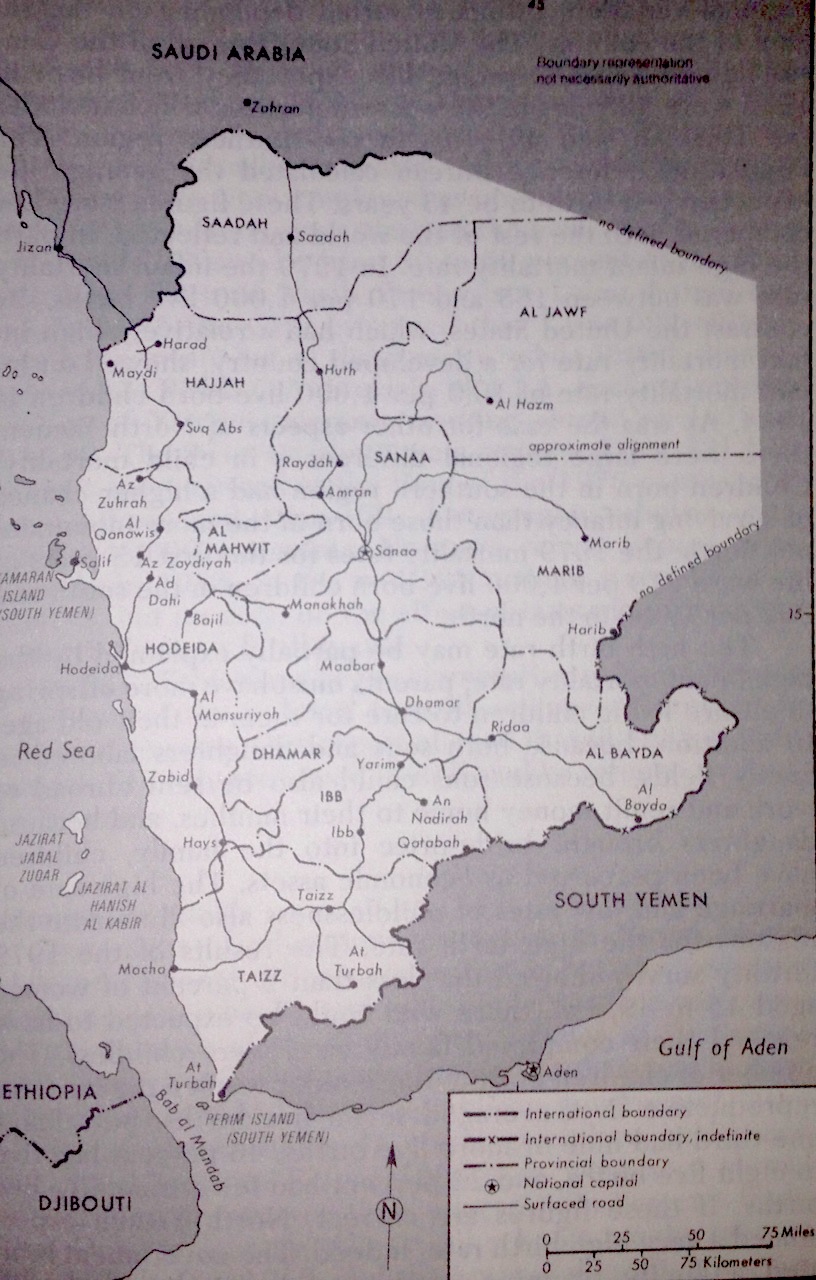

Map 4: North Yemen: Provinces, Major Cities, and Major Roads, 1984

Source: Krieger, Laurie, Darrel Eglin, Sally Ann Baynard, Donald Seekins, and Bahman Bakhtiari. The Yemens: Country Studies. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American University, Foreign Area Studies, 1986. 101. Print.

Female Education in the YAR

The first president of the YAR, Abdullah Al-Sallal, showed interest in improving female education, after all, the country witnessed minimal progress during the Imamate. During his inauguration ceremony in the city of Ta'izz, women were invited to participate in the celebration as an equal participant to men, which promised a better future under the YAR. The structure of the educational system was different than the PDRY; students had six years of primary education, three years of intermediate education, followed by three years of secondary education (Noman 2). Furthermore, the constitution of 1963 stated that education is a right for all Yemenis in article 32, and based on this, the Ministry of Education was created. The ministry created a system and a curriculum that emulated the educational system of Egypt. In turn, Egypt supplied the YAR with many educators to teach until the country had enough graduates to employ its own teachers. Many other countries lent a helping hand to Yemen; Saudi Arabia built schools, Kuwait paid the salaries of teachers, and Sudan sent employers to work as teachers (Boxberger 121). In 1969, a law was passed obligating university and higher education graduates of teaching in the country for two years prior to employment (Ba’abad 77-80). From 1963 to 1990, the YAR worked hard to improve education (see chart 3), but no specific sector was dedicated to women and only families that allowed their girls to go to school were educated.

Chart 3: Improvements in Middle School education from 1962 to 1990

Source: Ba'abad, 'Ali. Al-Ta'aleem Fee Al-Jumhooriah Al Yamaniyah [Education in the Yemeni Republic]. 7th ed. Sana'a: Maktabat Al-Irshad, 2003. 87. Print.

This lack of concern for women, carried out to other aspects of Yemeni society. Although the new country created a nationalist constitution (similar to that of Egypt’s), it took time to formulate laws concerning women. Family contentions in the YAR were settled in different ways according to Islamic law or Shari’a of the region. Zaydi courts used ijtihad (interpretation by the personal effort of a scholar) which treated each case as unique. This granted more rights to women than in Shafi’i courts where a single interpretation of the law applied. Many times family and women matters would be settled according to ‘urf or tribal law which is based on ahkam al-aslaf or rules of the ancestors (Molyneux, “Women’s Rights and Political Agency” 420). It was not until 1979, when Saleh came to power, that the YAR developed a National Family Law that incorporated Zaydi and Shafi'i jurisprudence. Overall, the laws followed the conservative and religious nature of the North; polygamy (as long as the husband practiced 'adl or equity) and talaq were permitted. Marriage age, for males and females, was legally set at 15 years old; however, it was not enforced. At times, when a family matter did not seem to be explained in the law, the adjudication was in the hands of the qadis or judges (Molyneux, "Women's Rights and Political Agency 419-420). Women's rights in the YAR seemed to lag behind those of the south; for example, women in the North gained the right to vote in 1983 while women in the south earned that right in 1970 (Khalife 10). For the most part, the approach to laws concerning women was heterogeneous due to the lack of a strong central state and granting women education was determined by individual families.

Gregory Johnsen, a native of Nebraska, wrote a book called The Last Refuge: Yemen, Al-Qaeda and America's War in Arabia. The book is divided into three main sections describing the presence of Yemenis in AlQaeda; first, in the war against the Soviets, followed by a phase of "Forgetting" then finally, the rise of a true Yemeni AlQaeda movement. The book just came out recently so it includes the developments that occurred during the Yemeni revolution. You can find the book here.

Gregory Johnsen, a native of Nebraska, wrote a book called The Last Refuge: Yemen, Al-Qaeda and America's War in Arabia. The book is divided into three main sections describing the presence of Yemenis in AlQaeda; first, in the war against the Soviets, followed by a phase of "Forgetting" then finally, the rise of a true Yemeni AlQaeda movement. The book just came out recently so it includes the developments that occurred during the Yemeni revolution. You can find the book here.